Imagine you’re a giant looking down on a city’s rooftops. Where you now see mostly grey, Prof. Youbin Zheng hopes to see green.

Planting more green roofs will help improve health and environment, says this adjunct professor in U of G’s School of Environmental Sciences (SES). Zheng leads a one-of-a-kind research team intended to cultivate an emerging industry of green roof providers and their greenhouse and nursery suppliers. Along with SES professor Mike Dixon, he runs a project developing green roof technology for northern climates. Last year the project received a three-year $161,000 grant from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

Green roofs – basically gardens covering rooftops – can provide several benefits, says Zheng. Like insulating caps, they help save energy. They can help manage stormwater by slowing runoff. Green roofs can help clean urban air, reduce the effects of urban heat islands and increase biodiversity. Built and maintained properly, they can even become “farms in the sky” to help feed more city dwellers.

If those benefits weren’t enough, there’s also a potential legal threat hanging over our cityscapes. Last year Toronto became the first North American city to require this environmental technology to be installed on new buildings with total floor space greater than 2,000 square metres. The Toronto bylaw applies to all new residential, commercial and institutional buildings, and will apply to industrial buildings beginning next year.

Zheng says before we install too many green roofs – and before other municipalities pass similar bylaws – we need to learn more about how to install and look after them. There’s more to growing a rooftop garden than dumping topsoil into boxes and rooting your favourite plants, as many building owners have learned the hard way.

“Plants normally produced for gardens may not be suitable for green roofs,” says Zheng, who has worked with nursery and greenhouse growers for 11 years. He’s now focusing on green roofs. “It grows in the garden, but does it work on the roof?” He aims to provide solid information for growers and installers within the next three years, based on studies here on campus.

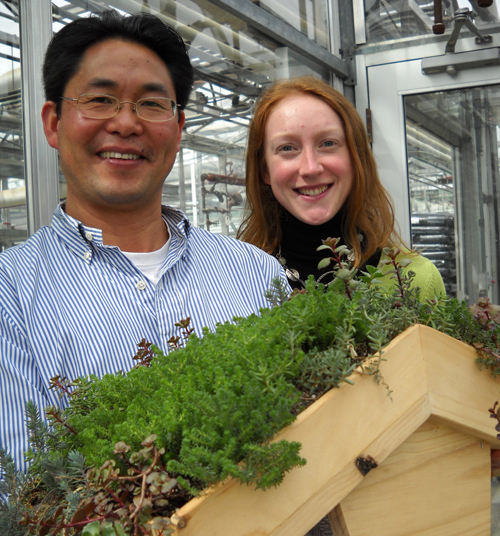

As the only research group of its kind in North America, the Guelph team of faculty, staff and students is using that OMAFRA funding to learn more about green roofs. Besides growing plants in the Bovey Building greenhouses, they’re testing “field plots” there, on area farms and on the science complex rooftop. The scientists develop and test growth mix (or substrate) and suitable plant species for the dry, too-hot or too-cold, and windy conditions normally found several storeys above the street.

Along with developing and testing growth medium recipes, they’re looking at which plants and combinations grow best in different substrates in varied roof conditions.

The backbone of many rooftop gardens is sedum, a succulent plant whose hundreds of species include kinds that tolerate drought or cold. In their campus plots, research assistants Mary Jane Clark and Katie Vinson also tend other plants, including artemisia, lamb’s ear, yarrow, grasses, catmint, juniper and pasque flower.

Says Clark: “I like the idea that, in urban settings, green roofs can provide a habitat for insects and animals.”

The researchers are also investigating basic fertilizer and watering regimens to help develop industry standards. What kinds of fertilizer to apply? How much? When? How and when to water? “We’re answering technical questions,” says Zheng.

He says green roofs are more common in Europe, including Germany and Scandinavia. Little research has been done in North America, including considering how to design buildings to bear the structure’s weight.

A green roof should last 50 years. Zheng says it costs two to three times as much as a conventional roof.

His project partners include Life Roof, Sedum Master, Landscape Ontario, Carrot Common and Flowers Canada-Ontario.

Less expensive green roofs with low-maintenance designs and materials are a kind of Holy Grail, says Mathis Natvik, a U of G master’s student.

In 2008, his Guelph company, Natvik Ecological, installed a green roof on the Delta Guelph Hotel and Conference Centre. That installation still contains its original plant community and has never been weeded, irrigated or fertilized.

Natvik says low-maintenance building standards in Europe have spurred installation of green roofs covering airport terminals, shopping malls and factories. “The largest roofs obviously make for the largest environmental benefits when greened with plants. We need research on how to create growing mediums and planting techniques for roofs like Pearson airport, which emit massive amounts of heat and inject massive amounts of water into the stormwater infrastructure.”

In Toronto, a total of more than 36,000 square metres of green roofs have been installed, including gardens at City Hall, the Metro Toronto YMCA, Ryerson and York universities.

For his master’s degree with Zheng, Greg Yuristy studies substrate materials for green roofs that are lightweight, sustainable and locally available. Among those components are recycled materials like crushed bricks. He’s interested in using roofs for growing food, a form of urban agriculture.

Zheng’s group plans to install a green roof at Toronto’s Carrot Common, an organic and health food store that plans to grow food on the roof. Growing food requires thicker substrate and lots of water, which work against the need for lightweight green roofs that the building can support.

In a whimsical turn, Yuristy installs green roofs on bird feeders he makes from reclaimed barn board and Plexiglas. Both Zheng and Dixon have installed his models in their home gardens.